What R the Differences in Art From Islam and India

Religious art, meanwhile, includes items of religious significance or those used for religious purposes. Not all religious art is Islamic art, while much of Islamic art is religious art—even if not manifestly so. Syrian forest inlay cabinets and tables may be used to concur alcohol, just their geometric patterns portray some of the loftiest realities of Islamic metaphysics and cosmology. Posters of Mecca and Medina or mass-produced prayer carpets emblazoned with the Kaaba are religious fine art only not Islamic fine art, despite the sacred architecture of the sites they describe. The recitation of the Qur'an in traditional maqāms and fifty-fifty the singing of inspired poetry in these modes and rhythms are both Islamic and religious art, whereas "Islamic" parodies of Justin Bieber songs and the popular motorcar-tuned, acapella qa śī dahs in four-part harmony may be religious, simply Islamic or sacred they certainly are not.

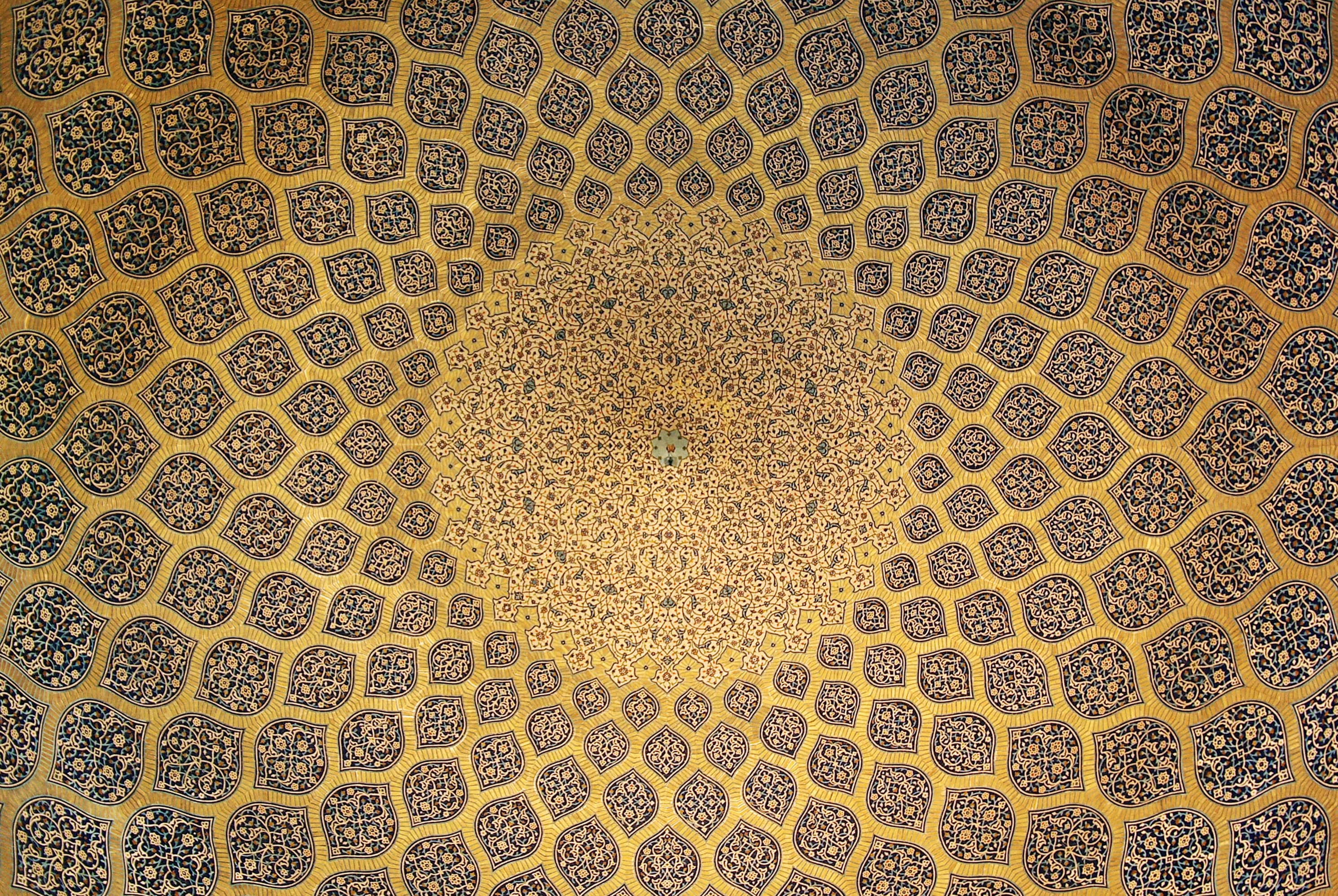

While difficult to define in concrete, formal terms, Islamic fine art is recognized easily, especially by those familiar with other dimensions of the Islamic tradition. Whether visual or sonoral, the Islamic arts project unity (taw ĥ īd), which manifests as symmetry, harmony, and rhythm—the imprint of unity on multiplicity. The Islamic arts do not mimic or imitate the outward forms of things but present their inner, archetypal realities, hence the emphasis on number (geometry) and letters (calligraphy), which are the basic building blocks of space/time and language. In traditional calligraphy, geometric ratios govern fifty-fifty the shapes and sizes of the letters, which gives the lettering fine art its remarkable harmony.

The Islamic arts also all carry the imprint of the Qur'an in terms of its meanings (ma¢ānī) and structures (mabānī). Like many sacred texts, many of the surahs and verses of the Qur'an have a chiastic, or ring, structure. That is, the concluding section mirrors the kickoff, the penultimate department mirrors the second, and so on, until the center, which contains the main theme or message. This symmetric, polycentric structure of overlapping patterns is clearly reflected in the geometric patterns of illumination that adorn Qur'anic manuscripts; the tessellations that adorn the mosques, madrasas, and homes where its verses are chanted; and even the structure of the musical maqāms in which it is recited.

Islamic art is founded on the interconnected sacred sciences of mathematics, geometry, music, and cosmology, not and so different from the medieval Christian notion of ars since scientia nihil est (art without science is naught). All of these sciences connect the multiplicity of creation to the unity of the Creator and engage the qualitative, symbolic aspects of multiplicity as well as its quantitative dimensions. Aristotle divided philosophy into three parts: physics, mathematics, and theology (ilāhiyyāt). Physics addresses the natural or material earth, and theology the divine, while mathematics (and the associated sciences of geometry and music, which are numbers in space and time, in the visual and sonoral domains, respectively) deals with the intermediate, archetypal, imaginal realm—the barzakh, between the divine and the terrestrial. These sciences of the intermediate realm allow the Islamic arts to serve every bit a ladder from the terrestrial to the celestial, from the sensory to the spiritual. They also accept their foundation in Islamic metaphysics and spirituality, which give the artists straight access to the spiritual realities and truths represented in their art.

Plato describes beauty every bit the splendor of the true; the disability to discern between dazzler and ugliness, therefore, corresponds to and accompanies the inability to discern between the truthful and the fake (al-bā ţ il). Harmonious and geometric, truthful beauty is timeless and reflects the beauty of the unseen, leading to tranquility and the remembrance of God. False dazzler, similar ugliness, is fleeting, discordant, and unbalanced, reflecting the chaos and multiplicity of the lower world and the lower levels of the human psyche, which leads to imbalance, dispersion, and heedlessness (ghaflah). It brings out the opaque aspect of creation that hides or veils the divine, whereas true beauty brings out the transparent or reflective attribute of things that makes them legible as signs of God.

The Two Streams of Islamic Art

Beauty is found in two things: in a verse, and in a tent of skin.

– Emir ¢Abd al-Qādir al-Jazā'irī

While the Islamic arts are many and diverse, they tin be roughly categorized into two domains: adab and ambience—that is, the arts of linguistic communication and those that create the surroundings in which people live (such as dress, architecture, urban pattern, and perfume). In precolonial times, both of these domains were nearly ubiquitous; they were part of the teaching of non merely Islamic scholars only all Muslims. Virtually all scholars studied, quoted, and wrote poesy. Many were masters of geometry; some were architects; while others, such as al-Fārābī and Amīr Khusrow, were main musicians. Even those scholars who were non accomplished artists were nurtured by the arts of adab, which they studied, and the arts of ambience that marked the institutions of their education. Some of the finest masterpieces of Islamic architecture are madrasas, such as the Bou Inania of Fes and Ulugh Beg in Samarqand, considering information technology was understood that architecture can support and nourish the soul, kindle the intellect, and nurture all the other Islamic sciences. Moreover, the arts of adab and ambience were not limited to mosques, madrasas, and palaces just determined the construction and form of the cities and homes in which Muslims lived, not to mention the utensils and tools they used; the dress they wore; and the melodies, poetry, and idioms that filled their hearts and flowed from their tongues. As Ananda Coomaraswamy notes, in traditional societies, "the artist was non a special kind of man, only every man a special kind of artist."

"Adab" is a word that is notoriously difficult to translate into English language. Meaning at one time "custom, culture, etiquette, morals, courtesy, decorum, and civilized comportment, as well as literature," to have adab is to be well-read and educated, to have expert manners, to be cultured or refined, and to take the wisdom to requite everything and everyone their due rights. The literature of adab is so named because it is designed to cultivate adab in its readers. Studying Islamic literature in the traditional fashion shapes and refines one's soul, intelligence, behavior, and voice communication according to the prophetic norm of elegance and eloquence.

The Prophet's married woman ¢Ā'ishah called the Prophet ﷺ "the Qur'an walking on earth," and the arts of adab nurture the creation of such character. Almost all works of Islamic literature are, in one way or another, commentaries on the Qur'an. Fifty-fifty the profane poetry of Abū Nuwās or al-Mutanabbī bears the imprint of the revelation in its language, images, idioms, and rhythms. The sophisticated belles-lettres of al-Jāĥiż, al-Ĥarīrī, Niżāmī, and Sa¢dī acuminate non merely the linguistic simply too the intellectual and moral faculties of their readers. The philosophical allegories of the Brethren of Purity, Ibn Sīnā, Suhrawardī, and Ibn Ţufayl draw on Qur'anic narratives and concepts, while integrating and inspiring the imagination and the intellect.

The influence of the Qur'an is even more axiomatic in the more than sacred works of adab, such as Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī's Mathnawī; ¢Aţţār'due south Man ţ iq al- ţ ayr; Ibn ¢Aţā' Allāh'southward Ĥ ikam; and the poetry of al-Būśīrī, Hafez, Ibn al-Fāriđ, Yūnus Emre, Amīr Khusrow, Ĥamzah Fansūrī, Shaykh Aĥmadu Bambā, Shaykh Ibrāhīm Niasse, and many others whose meanings, structures, styles, and fifty-fifty sounds closely mirror those of the Qur'an.13 These works of adab are similar lagoons that open up onto the ocean of the Qur'an, which in turn opens onto the divine reality. Works of adab bring the states closer to the Qur'an and bring the Qur'an closer to us: they train united states of america to read and interpret verses that have multiple levels of meaning, to read verses and stories from multiple perspectives, and to dive into their depths for pearls of meaning; they teach us how to read and live the Qur'an and Sunnah. In short, they cultivate adab.

Throughout Islamic history, most Muslims learned metaphysics, cosmology, and ethics through these poems and works of literature. To paraphrase a Southward Asian Muslim nawab's lament: "We lost our civilization and the living reality of our religion when nosotros stopped studying the Gulest ā n of Sa¢dī." Our grandmothers and grandfathers and the one-time generations of Muslims learned how to realize, alive, and put into practice the Qur'an and Sunnah, in large part, through the poems and works of the literature they memorized and studied, fifty-fifty if they could non read or write. The words of the eighth-century (second-century hijr ī) scholar and mu ĥ addith Ibn al-Mubārak seem even more truthful today: "Nosotros are more in need of acquiring adab (courtesy) than of learning hadith."

The traditional madrasa combines the learning of adab with the beautiful arts of ambience. Whether in the elaborate and ornate tessellation of the Ben Youssef madrasa of Marrakesh or nether the simple shade of a baobab tree in the Sahel, surrounded by God's artwork of nature, Islamic learning traditionally takes place in a beautiful ambient. This is significant and intentional, every bit i'due south surroundings have a profound touch on on 1'south thoughts. Contemplating the twin rosettes/stars on a Moroccan door helped me grasp the relationship between the divine essence and names, and their manifestations in the cosmos and the human being soul, and information technology was while gazing at the tiles in the Bou Inania madrasa in Fes that I realized the meaning of the metaphor describing God every bit "a circle whose heart is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere."

The nigh ubiquitous and important art that creates an Islamic ambience is the recitation of the Qur'an. This is the start and highest form of Islamic art, from which all others are derived. The precise art of tajwīd and the science of the maqāms, the musical modes in which the Qur'an is recited, bring out the beauty and geometry of the Qur'anic revelation as it was revealed to the Prophet ﷺ. In reciting the Qur'an, we participate in the divine deed of revelation and the prophetic human activity of reception, both of which have a profoundly transformative effect on our souls. The sound of Qur'anic recitation is an integral part of the soundscape of any Islamic metropolis or town and is nearly always arrestingly beautiful. This is significant considering in traditional Islamic civilization, truth (of which the Qur'an is the highest example) is ever accompanied by dazzler. In fact, dazzler is a criterion of the authentically Islamic. At that place is nothing Islamic that is non beautiful. This axiom governs every other traditional art of ambient, such every bit calligraphy; architecture and geometric design; music; and even dress, food, and perfume. Equally music plays such a prominent role in contemporary Western culture, it is important to examine music as an Islamic art more closely.

Many who know petty most music or Islam confidently proclaim that "there is no such matter as Islamic music" due to the lack of consensus about the condition of music in Islamic law. Beginning, it is important to distinguish the English term music from the Arabic mūsīqā. Although both are derived from the same Greek word meaning "the art of the muses," they have slightly dissimilar meanings and connotations. Whereas a native English language speaker would allocate the religious chanting of poetry, prayers, the adhān, or the Qur'an equally music or musical, these arts would not exist considered mūsīqā, which has the connotation of involving instruments and beingness non-religious. Similarly, the instrumental and vocal music (in the English sense) that accompanies some Sufi ceremonies is seldom considered mūsīqā; rather, it is called samā¢(audition) or dhikr (remembrance).

Nevertheless, instrumental music, whether mūsīqā or samā¢, remains controversial in the Islamic legal traditions precisely because of its tremendous power to elevate or debase the soul. Simply compare the beliefs of an audition at a heavy metal concert with that at a concert of Andalusian music. When criminals or soldiers pump themselves up to commit acts of violence, they seldom heed to the Indian classical music of Ali Akbar Khan. Traditional Islamic music has a remarkable ability to induce states of remembrance, peace, delectation, joy, courage, harmony, rest, and most especially honey and longing for the divine. The Islamic philosophers developed elaborate musical theories based on the principles of Pythagorean harmony to explain and refine preexisting folk traditions of music. Courtroom musicians produced a refined and refining fine art that served as the acoustic equivalent and accompaniment of adab, while the Sufi orders developed powerful traditions of spiritual music capable of transporting the soul into the divine presence. Although Islamic music differs widely from culture to civilisation, it has sure common features related to its Islamic cosmology and emphasis on taw ĥ īd. Information technology typically has a regular rhythm (rhythm is the banner of oneness across time), often increasing in pace toward the end of the song or concert, before dropping off into silence (which mirrors the acceleration of fourth dimension equally the final hour approaches); it oft includes ś alawāt or Qur'anic recitation; and it is characterized by a unity of melodic voices, eschewing the complex harmonies and multiple voices that characterize the all-time of Western music (e.one thousand., Bach), due to its emphasis on taw ĥ īd. For the skilled musician in an Islamic tradition, playing music is like praying with one's musical instrument, and for the prepared listener, it is similar listening to the wordless praise of the angels and the cosmos. As Seyyed Hossein Nasr notes, "Islamic civilization has not preserved and developed several great musical traditions in spite of Islam, but considering of information technology."fourteen

It is of import to note that music and other traditional Islamic arts not but belong to the by only are contemporary living traditions. All of these art forms are dynamic: they continually modify, adapt, and create new possibilities, all without departing from the fundamental principles of their particular form, the very principles that make them Islamic. These aforementioned principles tin can be applied to new art forms, such as web and graphic design, photography, and cinematography. The cinematic arts are primarily derived from the theater, which was never a major Islamic art, equally information technology was in the aboriginal Greek, Christian, and Hindu civilizations. In fact, Greek works of drama and theater were only well-nigh the merely works Muslims did not translate into Arabic, perhaps because the Islamic revelation is based more on a presentation of "the way things are" and not on the heroic sacrifice of a God-human being (Christianity) or on the myths nearly personified aspects of the divine (ancient Greek and Hindu traditions) that are repeated in liturgy and passion plays. The relatively non-mythological character of the Islamic tradition, and its emphasis on the unity and omnipotence of the divine, precluded dramatic tension within the divine or between homo heroes and the divine. Nonetheless, Persian Shi¢ism developed the drama of ta¢ziyeh depicting the events of the boxing of Karbala, and while not a primal sacred art, information technology was notwithstanding an of import Islamic religious art form. This is probably not unrelated to the fact that Iran has the most developed cinematic tradition of whatsoever Muslim country. Although some of Majid Majidi'south films come close, I believe a truly Islamic cinematic art has nonetheless to develop. Islamic cinema is not just movies about Islam or Muslims, or movie house made by Muslims, but the very philosophy and techniques of the fine art must be rooted in the Islamic perspective, much equally Bresson'southward work is rooted in Catholicism, Terrence Malik'southward work is rooted in a Heideggerian philosophy, and Tarkovsky's work is rooted in his own unique metaphysical vision influenced by Russian Orthodox Christianity.fifteen

All of the Islamic arts exist to back up the supreme art: the purification of the soul, the tillage of character, and the remembrance of God. "I was sent only to perfect the beauty of character," the Prophet ﷺ said. At that place is no question of "art for art's sake" in the Islamic arts because all of them accept practical, psychological, and spiritual functions. The Islamic arts are not a luxury; rather, they serve as essential supports for that fine art which is the raison d'être of Islamic law, theology, and indeed the unabridged Islamic tradition—the realization of the full potential of the human being land (and thus the entire cosmos, through humanity'southward role equally khalīfah) through the remembrance of God. The neglect of the Islamic arts has severely crippled the ummah's ability to pursue this highest art, both individually and collectively.

Tin can Fine art Heal Our Souls?

Know, O brother ... that the report of sensible geometry leads to skill in all the applied arts, while the written report of intelligible geometry leads to skill in the intellectual arts because this science is one of the gates through which we move to knowledge of essence of the soul, and that is the root of all knowledge.16

– Ikhwān al-Śafā

Beauty will save the globe.

– Fyodor Dostoevsky

As these epigrams suggest, the Islamic arts are gates through which we can admission the deepest truths of the cosmos, the revelation, and ourselves. The fail of these arts is a terrible blow, not but to our aesthetics just also to our ethical, intellectual, and spiritual lives. Just as our bodies, in a sense, go what we eat, our souls become what we look at, listen to, read, and think about. When the Islamic arts are rare, unrecognized, and underappreciated, what and then happens to our souls?

Just equally our bodies, in a sense, get what we eat, our souls become what we await at, listen to, read, and retrieve about. When the Islamic arts are rare, unrecognized, and underappreciated, what then happens to our souls?

The loss of the Islamic arts is also securely connected with the ascent of extreme sectarianism, the atrophy of the imaginal faculty, and the overall difficulty perceiving unity in multifariousness. In traditional Islamic cosmology and metaphysics, multiplicity and difference govern the outward world of appearances, whereas unity increases the farther one travels inwards, into the world of meaning and spirit. Because God is one, equally 1 approaches the divine presence, things become more unified. Those without access to this unity are unable to perceive and participate in the harmony—the reflection of unity in multiplicity—that links the world of appearances to that of realities. Imagination and the arts are bridges that unite these two worlds.

Dome interior of Shaykh Lutfollah Mosque

Those with a deep appreciation of the Islamic arts can appreciate thebarakah of and identify the profound realities represented in the architecture of Almohad Kingdom of morocco, Mamluk Egypt, or Safavid Iran completely irrespective of the official legal schoolhouse or theology of these dynasties. Moreover, those familiar with the profound principles of Islamic art cannot help but notice these same principles, admitting in a different mode, in the sacred arts of the other revealed religions. Islamic art, like Islam itself, synthesizes and confirms the traditions of sacred arts that came before it.17 Anyone familiar with the theory and principles of Islamic music cannot assist simply adore Bach, and those adept inadabwill find much to appreciate in the works of Shakespeare and Chuang Tzu, despite the great differences in the way the Muslim composer and these authors applied universal principles. In addition, anyone familiar with Islamic sacred geometry cannot fail to recognize the same principles at work in Buddhist and Hindu mandalas and temples.

This is precisely what Muslim scholars and artists have done for generations: understood, appreciated, and integrated the arts and sciences of other civilizations. One of the clearest signs of our decline has been the virtual disappearance of these constructed and creative intellectual and artistic processes. This has also been accompanied by increasing tensions between different Muslim groups and minority communities of other faiths that thrived in Muslim-majority lands for centuries. The Qur'an describes the variety of humanity every bit providential and divinely willed in order for u.s.a. to know one another, and through this cognition, to amend know ourselves and our God.xviii As Muslims lose affect with knowledge of our arts, of our history, of ourselves, of our tradition, and of God, we lose affect with reality and with the ability to recognize the truth and humanity of those who differ from us.nineteen

For Muslims who practice a arts and crafts, such equally the Islamic arts of calligraphy, poetry, or Qur'anic recitation, that arts and crafts provides them with a model for Islamic spirituality. A arts and crafts is an activity that requires continuous exercise and improvement over a lifetime, non a cookie-cutter mold into which one either fits or does not. If we view the purification of our hearts, the attempt to follow in the Prophet'south footsteps, and the quest to know God as a arts and crafts or an art form instead of as an identity, we can understand how dissimilar approaches can lead to the same or a similar goal. Thus, I believe the recent epidemic oftakfīr could be ameliorated by understanding the practice of Islam as an art form instead of focusing on an either/or notion of Muslim identity.

All is not lost, however. Discernment, whether intellectual or aesthetic, is difficult to recover once lost, simply the Qur'an says, "Inquire the people ofdhikr, if you practice non know" (21:07). Those Islamic societies and communities with thriving traditions of Islamic spirituality tend to take thriving artistic traditions, even if they are not economically wealthy (every bit in W Africa). This is because the practice of Islamic spirituality, being the science of taste (dhawq), refines ane's gustation, enabling recognition of spiritual truths and realities (ĥaqā'iq) in sensible forms; similarly, the Islamic arts support and refine the practice of Islamic spirituality. The revival of the arts must be a priority for Muslims worldwide considering the arts are vital to the rejuvenation of the Muslim listen and soul.twenty As Plato wrote, "The arts shall care for the bodies and souls of your people." While many have attempted to reduce the Islamic tradition to a listing of dos and don'ts in the realm of behavior and belief, the Islamic arts serve equally a powerful reminder of the more profound realities of the tradition, ofiĥsān, and of the purpose of the entire Islamic tradition in the first place: the highest fine art of bringing the human soul back to itsfiţrah, which perfectly reflects all of the divine names and qualities, both thejalāl (the majestic) and thejamāl (the beautiful).

Source: https://renovatio.zaytuna.edu/article/the-silent-theology-of-islamic-art

0 Response to "What R the Differences in Art From Islam and India"

Post a Comment